Posted on: November 18, 2019 by Simone Regina Adams Edit

Already in 2017, Andrew Winston wrote on medium.com about how differentiated the denial of the climate crisis is – including even what he calls “denying climate denial”.

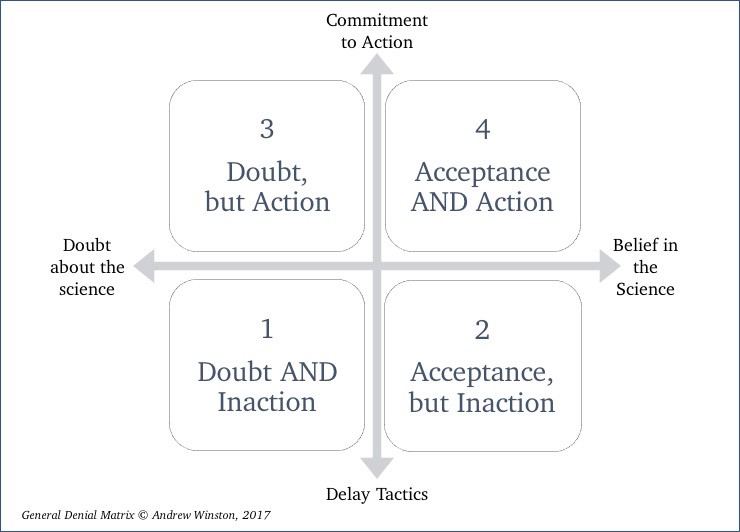

Winston creates a helpful differentiation by distinguishing between:

1. Whether we doubt the facts – or acknowledge the crisis, and

2. Whether we act – or remain passive.

This results in four different ways of argumentation and approaches – which is actually to be observed again and again.

Venice, St. Mark’s Square in November 2019

In April 2017, New York Times columnist, Bret Stephens, wrote: (1) Everyone supporting climate action is too certain on the science (and science is never 100%), and (2) it’s too expensive to do something.

Both are fake arguments.

However, Stephens does not see himself as a denier of the climate crisis, he wrote, after there was some excitement about his column: “None of this is to deny climate change or the possible severity of its consequences.”

This discussion led Andrew Winston to differentiate the various types of denial: it is not limited to the denial of basic science in total. The defense is more sophisticated and thus even more dangerous.

He demonstrates this with an example: “Imagine, your doctor (by “doctor”, I mean the entire medical establishment) tells you that you have a dangerously high cholesterol and blogged arteries. She says you might drop dead soon. (Or, to keep track of the climate crisis, 97 out of 100 doctors say the same thing).

He now differentiates between four possible responses that are based on two dimensions: 1. belief in the basic facts (or doubts); and 2. whether you commit to action or postpone any necessary action.

- Doubt and inaction (simplistic denial). You say, “I don`t think the evidence is real – it`s a hoax.”

- Acceptance, but inaction: “Yes, it’s happening, but I don’t think aggressive action is warranted yet. It may disrupt my life too much.”

- Doubt, but action: “I’m not sure the doctor is right. But I’ll take the healthier path because the risk is too high, and it’s better for me anyway.”

- Acceptance and action: “I believe the doctor and the science and I think it’s urgent. So I’m dramatically changing my behavior, and doing it now.”

If option 1 seems silly to you — because, say, you’re having trouble climbing stairs without wheezing, so the evidence is already there — you’ve got three options left. You may choose path 4, where you realize that the problem is real and change your behavior accordingly. But since outcomes are all that matter, path 3 is nearly as good. Regardless of why, you could eat healthier, exercise more, and take a statin. You might see that the behavior change has many additional benefits — you feel better all the time, live longer, and be able to do more with your life.

But it’s path 2 — acknowledging the issue, but arguing for more discussion and delay — that must drive doctors crazy.”

Denying that we need to act aggressively and immediately is still denial. And it’s really dangerous.

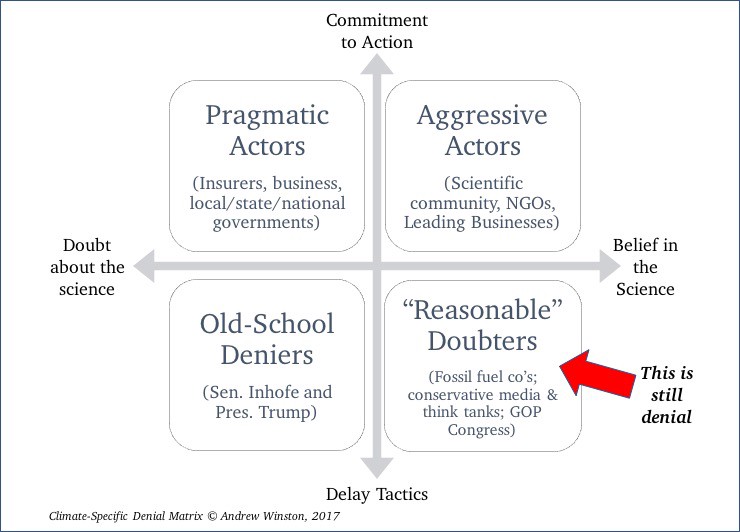

What that means for American politics and economics is also explained by Winston. He writes:

“For many years, the mainstream of climate denial took path 1. So far, at least on Twitter, our president is still here – along with diehard deniers like Senator Inhofe, he of the famous snowball on the Senate floor. All of us who see the urgency — which includes all major scientific bodies, the big environmental NGOs, and leading businesses and clean tech players — are solidly in camp 4. In my experience, the majority of big business sit roughly in camp 3 today, taking a pragmatic approach and moving to renewable energy, for example, as it gets much cheaper (but they’re pretty far right within bucket 3, about to tip into bucket 4 — climate science denial is disappearing within the business community) .

Group 1 is on the sidelines of any serious debate about the future of energy or commerce. It’s ludicrous to keep denying the basics here. So, to stay within the normal realm of discourse, many commentators and politicians have moved into group 2 of “Reasonable” Doubters. People like Bret Stephens suggest more discussion and debate about whether action is really necessary and worth the “cost” (ignoring — and, yes, denying — that if we do nothing it will likely cost the world many trillions more than if we build the clean economy).

Let me be clear: denying that we need to act aggressively and immediately is still denial. And it’s really dangerous. So let’s call it climate action denial. Denial in the form of faux support for reasoned discussion is just a more nuanced technique for defending the status quo. Of course we need discussion, but about how we move forward and take carbon out of the economy — and maybe even out of the atmosphere — in the most economic way. And we need to discuss how to help those left behind as the clean economy sweeps through the world.

But the time for discussion of whether we should act fast is long gone. It’s a simple risk-reward equation, and the risks are more clear than ever, as are the rewards, as the cost of building the clean economy plummets.

The new form of denial is to continue the myth that it’s way too expensive to do anything or say, “hey, what’s wrong with some debate.” It is denial to ignore literally decades of very clear and alarming science, and then argue for going slow when we have no time.